True biomimetic innovation is not about copying nature’s forms, but reverse-engineering its fundamental principles of physics and chemistry.

- Energy reduction breakthroughs come from understanding the “how” behind a biological success, not just the “what”.

- Translating these principles into industrial applications involves complex, multiscale challenges, from macro-level airflow to nano-scale adhesion.

Recommendation: Shift your design focus from mimicking aesthetics to abstracting and applying the core functional strategies that allow natural systems to thrive with maximum efficiency.

For decades, architects and designers have looked to nature for inspiration, often citing the elegant spiral of a nautilus shell or the strength of a spider’s web. This approach, however, frequently remains superficial—a quest for aesthetic novelty rather than a deep dive into functional efficiency. We see the common examples, like termite mounds for cooling or shark skin for drag reduction, presented as simple, almost magical solutions. But this misses the point entirely and leads to designs that are complex, costly, and often fail in the real world.

The core frustration for innovators in this field is the gap between a biological marvel and a viable, manufacturable product. The real challenge isn’t identifying nature’s successes; it’s understanding and translating the underlying physical, chemical, and structural engineering that makes them possible. Why does a specific texture reduce drag? How does an organism achieve powerful adhesion without toxic glues? The answers lie not in the final form, but in the intricate mechanics at play across multiple scales.

This article shifts the perspective. We will move beyond the “what” and explore the “how.” Instead of merely cataloging nature’s inventions, we will investigate the engineering principles that biomimicry allows us to unlock. We will examine not only the celebrated successes but also the critical failures, because it is in understanding the constraints and translation errors that true innovation is born. This is a journey from simple imitation to profound functional abstraction, where nature becomes less of a catalogue and more of an R&D department with 3.8 billion years of experience.

This guide will deconstruct several key biomimetic concepts, revealing the engineering principles that drive their energy-saving potential. By exploring these case studies, you will gain a deeper understanding of how to apply these strategies in your own work.

Summary: A Guide to Nature-Inspired Architectural Efficiency

- Why Termite Mounds Hold the Secret to Zero-Energy Air Conditioning?

- How to Reduce Fuel Drag by 5% Using Shark Skin Textures?

- Chemical Glues or Gecko Adhesives: Which Is the Future of Assembly?

- The Flexibility Error That Makes Bio-Robots Fail in Real Terrain

- Problem and Solution: Harvesting Water in Arid Climates Using Fog Nets

- How to Improve Your Car’s Aerodynamics With Simple Aftermarket Parts?

- Newtonian vs. Quantum Mechanics: Which Rules Apply to Nanotechnology?

- Why Are Modern Cars Becoming Impossible to Repair at Home?

Why Termite Mounds Hold the Secret to Zero-Energy Air Conditioning?

The termite mound is a classic example of biomimetic architecture, but its genius is often misunderstood. It’s not the shape of the mound itself that’s magical, but the sophisticated system of passive thermal regulation it embodies. Termites in sub-Saharan Africa build mounds that maintain a near-constant internal temperature of 30°C, even as outside temperatures swing from over 40°C during the day to near freezing at night. They achieve this through a process of functional abstraction we can replicate: buoyancy-driven ventilation.

The system works through a network of tunnels and a central “chimney.” Hot air generated by the termites’ metabolic activity and fungal gardens rises and exits through the top of the mound. This creates negative pressure, drawing cooler air in through lower-level vents. The porous structure of the mound itself acts as a lung, exchanging gases with the outside air through a complex network of micro-tunnels. This is a masterful lesson in using natural convection and thermal mass to create a self-cooling system.

Architects have translated this principle into buildings like the Eastgate Centre in Harare, Zimbabwe. By studying the mound’s structure, designers created a building that uses a similar passive cooling system of atriums and vents. The result is staggering: a report from the World Economic Forum highlights that buildings using termite-inspired passive cooling systems consume 90% less energy for climate control than conventional buildings of the same size. This demonstrates that the true innovation lies in understanding the core principle—managing air pressure and flow—rather than simply building a termite-shaped structure.

How to Reduce Fuel Drag by 5% Using Shark Skin Textures?

At a completely different scale, shark skin offers a profound lesson in fluid dynamics. While appearing smooth from a distance, a shark’s skin is covered in microscopic, tooth-like structures called dermal denticles. These are not passive scales; they are precisely shaped and aligned riblets that actively manipulate the flow of water over the shark’s body. Their function is to reduce drag and turbulence, allowing the shark to move through water with exceptional efficiency.

The engineering principle at work is the control of the boundary layer—the thin layer of fluid directly in contact with a moving surface. In turbulent flow, chaotic vortices form in this layer, creating pressure drag that slows an object down. The shark’s riblets are spaced to prevent these vortices from forming, keeping the boundary layer more stable and “attached” to the skin. This significantly reduces friction drag. It’s a highly optimized solution for a specific problem: efficient movement in a dense fluid.

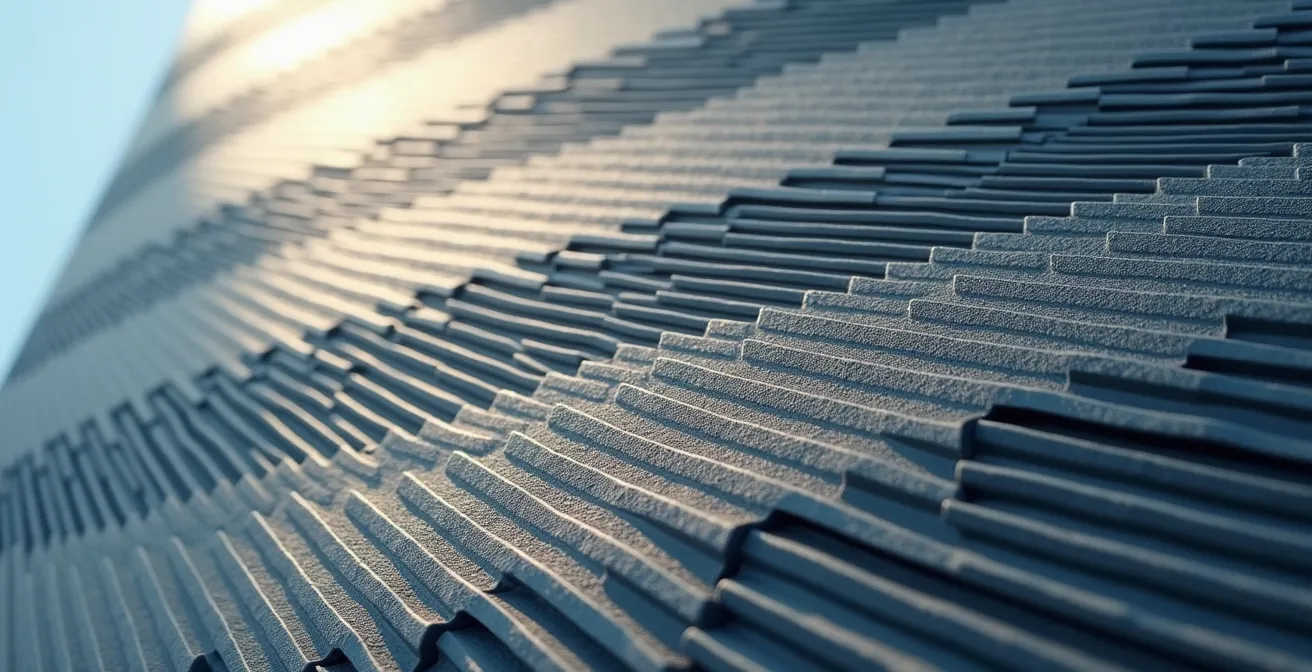

This principle of `multiscale mechanics` is now being translated to architecture and transportation. By applying similar micro-textures to the surfaces of airplanes, ship hulls, and even the facades of skyscrapers, we can reduce wind or water resistance. An airplane with a riblet-textured fuselage can see a reduction in fuel consumption, while a building clad in biomimetic panels experiences lower wind loads, reducing the need for heavy, energy-intensive structural reinforcement. This is a clear example of how a nano-scale biological feature can have a macro-scale impact on energy consumption.

As this image illustrates, the precise geometry of the riblets is critical. The translation from biology to manufacturing requires advanced nano-engineering to replicate these patterns on materials like composite panels or films. The challenge lies in achieving this precision at scale and ensuring the texture’s durability against environmental wear and tear, a key aspect of `system integration`.

Chemical Glues or Gecko Adhesives: Which Is the Future of Assembly?

The world of industrial assembly is dominated by chemical adhesives and mechanical fasteners. While effective, these methods often involve toxic solvents, are permanent (hindering recycling and repair), and fail in extreme conditions. Nature, however, has evolved a radically different approach: dry adhesion. The gecko is the master of this, able to scale sheer glass walls and hang from a ceiling by a single toe, all without any sticky residue.

The secret is not a chemical glue but a triumph of physics at the nano-scale. A gecko’s footpads are covered in millions of microscopic hairs called setae. Each seta splits into hundreds of even smaller tips called spatulae. This immense proliferation of contact points allows the gecko to leverage a weak intermolecular force known as van der Waals forces. While negligible at a macro scale, the cumulative effect of these forces across billions of spatulae creates an incredibly strong, yet instantly reversible, bond.

Translating this requires a shift in thinking from chemical bonding to physical interaction. Engineers are developing “gecko-tape” with synthetic micro-structures that mimic setae. These adhesives are dry, reusable, and leave no residue. In architecture and manufacturing, this technology promises a revolution in “Design for Disassembly.” Imagine modular wall panels, facade elements, or internal components that can be installed, removed, and replaced with ease, held in place by switchable, biomimetic adhesives. This not only simplifies maintenance but also makes buildings fundamentally more adaptable and recyclable, drastically reducing their lifecycle energy footprint.

The Flexibility Error That Makes Bio-Robots Fail in Real Terrain

While biomimicry offers incredible solutions, it also provides crucial lessons through failure. One of the most common pitfalls is the “flexibility error,” particularly evident in the field of bio-robotics. Designers, inspired by the fluid movement of animals like cheetahs or snakes, create robots with highly flexible and compliant structures. The goal is to replicate nature’s grace and adaptability. In a controlled lab environment, these robots perform beautifully.

However, when deployed in real, unpredictable terrain, they often fail. The problem lies in a misunderstanding of controlled stiffness. An animal’s movement isn’t just about flexibility; it’s a dynamic interplay between flexible joints and muscles that can become momentarily rigid to provide stability and power. A cheetah’s spine flexes to lengthen its stride, but its legs become stiff pillars upon impact to transfer force into the ground. It’s not just flexible; it’s variably compliant.

Many early bio-robots were simply too flexible. They lacked the ability to selectively stiffen their structures, leading to a loss of control, an inability to handle unexpected loads, and inefficient energy transfer. This is a critical error in `translation fidelity`. The design copied the form of flexibility but missed the function of dynamic stiffness control. Modern bio-inspired robots now incorporate materials and actuators that can change their stiffness on demand, more accurately reflecting the muscular-skeletal systems they emulate. This lesson is vital for architecture too: a building that is designed to be “flexible” to withstand wind or seismic loads must also have systems for controlled damping and rigidity, otherwise it risks catastrophic resonance.

Problem and Solution: Harvesting Water in Arid Climates Using Fog Nets

In some of the world’s most arid regions, life has found ingenious ways to harvest water directly from the air. The Namib desert beetle is a prime example of biomimicry offering a direct solution to a critical human problem: water scarcity. This beetle survives by collecting moisture from the morning fog on its back, a feat made possible by its shell’s unique surface properties.

The beetle’s back is covered in a pattern of microscopic, hydrophilic (water-attracting) bumps on a superhydrophobic (water-repelling) waxy surface. As fog rolls in, tiny water droplets collect and coalesce on the hydrophilic bumps. Once a droplet becomes large enough, its weight overcomes the adhesion, and it rolls down the hydrophobic surface directly into the beetle’s mouth. It is a highly efficient, passive water collection and transport system.

This dual hydrophilic-hydrophobic principle is a powerful tool for architects and engineers. As the illustration shows, building facades, roofing materials, and even large-scale “fog nets” can be designed with similar surface texturing to capture atmospheric moisture. In coastal or mountainous regions with frequent fog but little rain, these systems can provide a sustainable source of potable water for communities or for a building’s greywater needs, significantly reducing reliance on energy-intensive water pumping and purification.

Case Study: The Namib Desert Beetle Principle in Architecture

Water collection systems inspired by the Namib desert beetle are a prime example of functional biomimicry. According to an analysis by designers at Pablo Luna Studio, this beetle’s ability to collect moisture from the air through tiny, hydrophilic bumps on its back, which funnel water droplets, serves as a direct blueprint. In architecture, this mechanism is applied to create building surfaces that capture and direct rainwater or ambient humidity, dramatically improving water efficiency and reducing a building’s ecological footprint in arid environments.

How to Improve Your Car’s Aerodynamics With Simple Aftermarket Parts?

While this article focuses on architecture, the principles of biomimetic design are universal. The challenge of moving an object efficiently through a fluid—be it a building in the wind or a car on the highway—is fundamentally the same. The lessons learned from shark skin and fish fins can be directly applied to improve the aerodynamic performance of vehicles, often through surprisingly simple, bio-inspired retrofits.

One key concept is the management of air separation. As air flows over a car’s body, it can detach from the surface, especially at the rear, creating a large wake of turbulent, low-pressure air. This turbulence is a major source of drag. Many marine animals use small fins and ridges to control this flow separation. This is the principle behind vortex generators. These are small, fin-like tabs that can be placed on a car’s roof or trunk. They create tiny, controlled vortices that energize the boundary layer, helping it stay “attached” to the car’s body for longer. This reduces the size of the wake and, consequently, lowers aerodynamic drag, improving fuel efficiency.

Another example is surface texturing, akin to the dimples on a golf ball (a design also inspired by natural patterns). While a smooth surface seems most efficient, a strategically textured surface can, like shark skin, maintain a turbulent boundary layer that is more resistant to separation than a laminar one, ultimately reducing overall drag in certain conditions. Applying these principles, which are rooted in the deep observation of natural systems, allows for intelligent, targeted modifications that enhance performance without requiring a complete redesign. It’s about making smart, incremental improvements based on proven evolutionary strategies.

Newtonian vs. Quantum Mechanics: Which Rules Apply to Nanotechnology?

To truly master biomimetic engineering, one must appreciate that nature operates under different sets of physical laws at different scales. When we design a building, we are primarily in the world of Newtonian mechanics: gravity, stress, strain, and macroscopic forces dictate the structure. A beam’s strength and a column’s load-bearing capacity are calculated using these classical principles.

However, when we delve into the secrets of the gecko’s foot or the iridescent sheen of a butterfly’s wing, we enter the realm of nanotechnology, where the rules change. At this scale, forces like gravity become almost irrelevant, while quantum-level phenomena like van der Waals forces and electron tunneling become dominant. The gecko’s adhesion, as we’ve seen, is not a function of its mass or strength in a Newtonian sense; it is a product of molecular-level quantum interactions.

This distinction is the source of many `translation fidelity` challenges. An engineer cannot design a gecko-inspired adhesive using the same formulas used to design a bridge. It requires a fundamental shift in perspective and expertise in material science and quantum physics. The iridescent, color-shifting properties of some beetle shells are not created by pigments, but by nano-structures that refract light—a phenomenon called structural coloration. Replicating this for a paint-free, durable building facade requires manipulating materials at a scale where classical optics give way to wave-particle duality. Understanding which set of physical laws governs the biological trait you are studying is the first and most critical step in its successful translation.

Key Takeaways

- Biomimetic success relies on abstracting nature’s functional principles, not just copying its forms.

- Solutions operate at multiple scales, from macro-level airflow (termite mounds) to nano-level forces (gecko adhesion).

- Real-world implementation requires addressing `life-cycle constraints` like maintenance, repairability, and material durability, which are often the biggest hurdles.

Why Are Modern Cars Becoming Impossible to Repair at Home?

The question of repairability in modern cars serves as a powerful, if cautionary, metaphor for the challenges facing complex biomimetic systems. A modern car, like a high-performance biomimetic building, is a highly integrated system of systems. Its efficiency is born from the seamless interaction of mechanical, electronic, and software components. However, this very integration, which provides the performance benefits, also creates a “black box” that is difficult to diagnose, maintain, or repair without specialized tools and knowledge.

This is the critical challenge of system integration in biomimicry. When we create a building with a responsive facade, a passive cooling system, and a water-harvesting surface, we are not just adding features; we are creating an ecosystem. The failure of one component can have cascading effects on the others. If the sensors controlling the responsive facade fail, does the passive cooling system have to work harder, negating its energy savings? Who is trained to maintain the hydrophilic surface coating on a 30-story building? These are the `life-cycle constraints` that can make a theoretically brilliant design an operational nightmare.

The difficulty of translating concepts into built forms is a major barrier. As Novatr Architecture Review points out, “Difficult to translate the concepts into built forms: Perhaps the greatest challenge in biomimetic architecture is actually building the structures that have been conceptualised. This has constrained the field to a certain degree because construction technology that was capable of creating these complex structures did not exist until recently.” This highlights the gap between concept and reality. Without a plan for maintenance and lifecycle management, even the most innovative designs are destined to fail. True sustainability isn’t just about initial energy savings; it’s about long-term viability, repairability, and resilience.

The success of this field is contingent upon the cohesive collaboration of a few people with a wide range of knowledge. They all originate from different backgrounds with different technical languages and different approaches, and thus collaborating can be challenging, to say the least.

– Novatr Architecture Review, What is Biomimetic Design in Architecture

Action Plan: Auditing Your Design for Biomimetic Maintainability

- Points of contact: List all specialized components in your design (e.g., kinetic facade actuators, specialized surface coatings). Who is the supplier? What is the maintenance protocol?

- Collecte: Inventory existing maintenance plans. Are they designed for conventional systems? Do they account for the unique failure modes of your biomimetic components (e.g., bio-fouling on a textured surface)?

- Cohérence: Confront the maintenance plan with the design’s core sustainability goals. Does a difficult-to-replace component undermine the lifecycle energy savings?

- Mémorabilité/émotion: Identify which systems are ‘black boxes’ versus those that are transparent and diagnosable. Can facility managers understand the system’s logic, or do they just see an error code?

- Plan d’intégration: Develop a prioritized training and documentation plan. Focus first on the components most critical to the building’s core function and most likely to fail.

Therefore, the next step for any designer or architect is to move beyond inspiration and adopt a rigorous, principle-driven methodology. Begin by deconstructing biological successes into their core functions and assess their translatability not just for performance, but for manufacturing, integration, and long-term maintenance.