Aerodynamic drag is not just for race cars; it’s a measurable tax on every mile you drive, responsible for a significant portion of your fuel consumption at highway speeds.

- Your vehicle’s shape—its drag coefficient (Cd) combined with its frontal area—is the primary factor dictating this invisible “tax.”

- External accessories like roof boxes can impose a severe fuel penalty of up to 25%, a cost that persists even when the box is empty.

Recommendation: Understanding and managing airflow—through smart modifications, accessory removal, and refined driving habits—is the most effective way to reduce this invisible cost and improve your MPG.

As you settle in for a long highway drive, you watch the fuel gauge, an all-too-familiar source of anxiety. Most drivers attribute its steady decline to engine size or tire pressure, following common advice to slow down or keep tires properly inflated. While these factors are important, they overlook the single most dominant force working against your vehicle at speed: aerodynamic drag. This invisible resistance is a physical tax levied on every mile per hour you travel, growing exponentially stronger the faster you go.

Many discussions on fuel economy stop at generic tips. They fail to explain the fundamental physics that govern why a boxy SUV costs so much more to run on the highway than a sleek sedan. The real key to unlocking significant fuel savings doesn’t lie in a simple checklist, but in mastering the principles of airflow. It’s about understanding concepts like flow separation and the turbulent wake—the pocket of chaotic, low-pressure air that literally pulls your car backward.

But if the solution isn’t just about buying a “more aerodynamic car,” what is it? The answer lies in a deeper understanding of how your vehicle’s specific shape, the accessories you attach to it, and even your moment-to-moment driving decisions manipulate this invisible force. This guide moves beyond the platitudes. It provides an aerodynamicist’s perspective, breaking down the science of drag into tangible, wallet-focused insights. We will dissect how design choices create drag, how simple modifications can manage it, and how conscious driving techniques can help you conquer it.

For those who prefer a visual breakdown, the following video offers a focused look at how a common aerodynamic component, the front splitter, functions to manage airflow and improve stability, illustrating one of the core principles we will discuss.

To help you navigate these principles, this article is structured to build your understanding from the ground up. We will start with the fundamental reasons for energy loss at speed and progress to actionable strategies you can implement to reduce the aerodynamic tax on your wallet.

Table of Contents: A Deep Dive into How Aerodynamics Affects Fuel Costs

- Why SUVs Consume 30% More Energy at Highway Speeds?

- How to Improve Your Car’s Aerodynamics With Simple Aftermarket Parts?

- Active Grille Shutters or Fixed Spoilers: Which Saves More Fuel?

- The Roof Box Mistake That Kills Your Highway Mileage

- When to Roll Up Windows and Use A/C to Reduce Drag?

- How to Reduce Fuel Drag by 5% Using Shark Skin Textures?

- Newtonian vs. Quantum Mechanics: Which Rules Apply to Nanotechnology?

- How to Achieve 20% Fuel Savings Through Driving Habits Alone?

Why SUVs Consume 30% More Energy at Highway Speeds?

The primary reason an SUV or truck consumes vastly more fuel than a sedan at highway speeds comes down to a simple physics equation where two variables are paramount: the drag coefficient (Cd) and the frontal area (A). The drag coefficient is a measure of how aerodynamically “slippery” a shape is, while the frontal area is simply the vehicle’s cross-section as seen from the front. The total aerodynamic drag is a product of these two factors, and SUVs are at a disadvantage on both counts.

Modern sedans are meticulously engineered for low drag, with typical Cd values between 0.25-0.30 for modern sedans, whereas SUVs land between 0.35-0.45. This difference may seem small, but its effect is substantial. A higher Cd means the air has more trouble flowing smoothly over the body, leading to earlier flow separation. This creates a larger, more turbulent low-pressure zone behind the vehicle—the “turbulent wake”—which acts like a vacuum, pulling the car backward and forcing the engine to work harder just to maintain speed.

This principle is starkly illustrated when comparing specific models. The boxy, upright profile of a vehicle like the Jeep Wrangler results in a drag coefficient over 0.40. In contrast, a sleek, modern crossover like the Tesla Model Y, designed with aerodynamics as a priority, achieves a Cd of approximately 0.23. At 70 mph, the Wrangler requires significantly more horsepower purely to overcome air resistance. This difference in aerodynamic efficiency directly translates to the 20-30% higher fuel consumption observed in less streamlined vehicles at highway speeds, a direct and continuous tax on a less efficient design.

How to Improve Your Car’s Aerodynamics With Simple Aftermarket Parts?

While you cannot change your vehicle’s fundamental shape, you can influence how air interacts with it, particularly at the front and underneath the car. The goal of most simple aerodynamic modifications is to either guide air away from high-drag areas (like wheels and the rough underbody) or to reduce the amount of air that flows underneath the vehicle, where it creates lift and turbulence. These are not just for aesthetics; they are functional tools for managing airflow.

Common aftermarket parts like front air dams (or splitters), side skirts, and underbody panels are all designed with this in mind. An air dam, for instance, reduces the volume of air going under the car, minimizing turbulence created by exposed suspension and exhaust components. Small deflectors, sometimes called “spats,” placed in front of the tires can guide air smoothly around the wheels instead of letting it hit the flat, rotating surface head-on. Even small, seemingly minor additions can have a measurable effect by promoting a more attached, or laminar, flow of air along the car’s body.

As the image above illustrates, these components are designed with precision to alter the airflow at critical points. The front splitter channels air around the car, while deflectors near the wheel well prevent air from entering the turbulent wheel arch. For the fuel-conscious driver, the key is to choose parts that are designed for drag reduction, not just aggressive styling. Many “performance” parts are designed to increase downforce for racing, which can often increase drag and harm fuel economy.

Action Plan: Auditing Your Vehicle’s Aerodynamic Profile

- Baseline Test: First, establish a baseline. Use a GPS app on a quiet, flat road to perform a coast-down test (e.g., from 60 mph to 50 mph) and record the time. This is a proxy for your current drag.

- Front Airflow Management: Install a front air dam. Its purpose is to reduce the volume of high-pressure air that flows under the vehicle, which is a major source of turbulence and lift.

- Wheel Turbulence: Add small wheel spats or air curtains in front of the rear tires. These simple deflectors guide air around the turbulent wheel areas rather than letting it get trapped.

- Underbody Smoothing: Install smooth underbody panels. The underside of most cars is a chaotic mess of components that creates significant drag. Panels create a smooth surface for air to flow across.

- Verification: After installing modifications, repeat the coast-down test under identical conditions. A longer coast-down time indicates a successful reduction in aerodynamic drag.

–

Active Grille Shutters or Fixed Spoilers: Which Saves More Fuel?

When considering aerodynamic enhancements, it’s crucial to distinguish between parts designed to reduce drag and those designed to manage lift. Two common features, active grille shutters and fixed rear spoilers, serve very different purposes, and their impact on your wallet differs accordingly. The magnitude of these changes is often small, but as Max Schenkel, a GM Technical Fellow in Aerodynamics, notes, they are meticulously measured.

For a full-size truck, a change in drag coefficient of 0.01 is approximately equal to an improvement in fuel economy of 0.1 mpg on the combined city/highway driving cycle.

– Max Schenkel, GM Technical Fellow, Aerodynamics

This context shows that even small aerodynamic tweaks have a real, if modest, effect on fuel consumption. Active grille shutters are a pure drag-reduction technology. At low speeds or when the engine is cold, the shutters remain open to allow cooling air to the radiator. However, at highway speeds, when sufficient airflow is present, they close automatically. This prevents excess air from entering the turbulent engine bay and forces it to flow smoothly over and around the car’s hood, reducing overall drag. Their benefit is adaptive and intelligent.

A fixed rear spoiler, conversely, is primarily a tool for managing lift. At high speeds, it generates downforce on the rear axle, increasing stability. However, this often comes at the cost of increased drag. While some spoiler designs can slightly improve fuel economy by “cleaning up” the airflow leaving the trunk and reducing the size of the turbulent wake, many aftermarket spoilers are designed for looks or performance and can actually worsen your MPG. The choice between them depends entirely on the driving conditions.

To make a financially sound decision, it is essential to compare their specific benefits and costs, as detailed in a recent comparative analysis.

| Feature | Active Grille Shutters | Fixed Spoilers |

|---|---|---|

| Fuel Economy Improvement | 1-2% overall | 0.5-1.5% at highway speeds |

| Best Use Case | Highway cruising & cold weather | Consistent highway driving |

| Initial Cost | $500-1500 (factory option) | $200-800 (aftermarket) |

| ROI Break-even | 15,000-30,000 miles | 10,000-20,000 miles |

| Maintenance | Electronic components may fail | No maintenance required |

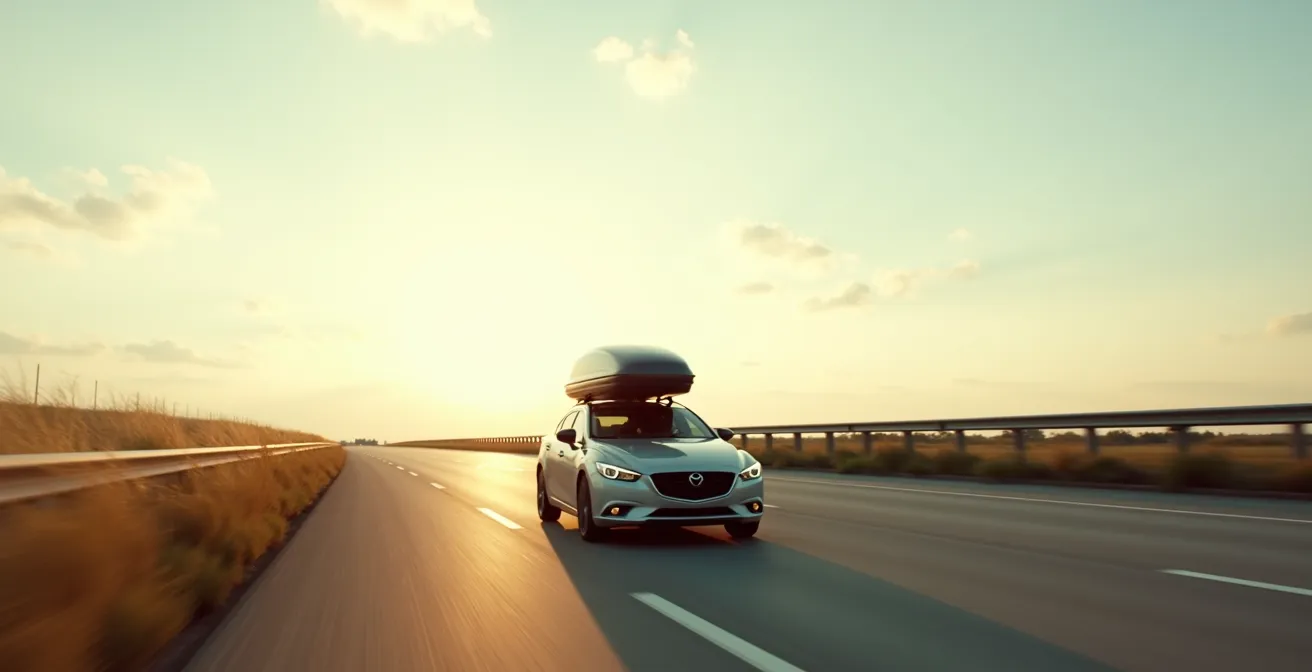

The Roof Box Mistake That Kills Your Highway Mileage

Of all the modifications a driver can make, adding a roof-mounted cargo box is arguably the most detrimental to aerodynamic efficiency. While incredibly useful for increasing storage, its impact on your fuel budget is severe and often underestimated. The U.S. Department of Energy states that rooftop cargo carriers can reduce fuel economy by 10-25% at highway speeds. This isn’t a minor penalty; it’s equivalent to downgrading your vehicle’s efficiency by several classes.

The reason for this drastic effect is twofold. First, the box significantly increases the vehicle’s frontal area, forcing it to push a larger column of air out of the way. Second, and more importantly, it introduces a massive source of turbulence and parasitic drag. The airflow, which was designed to move smoothly over your car’s roof, is violently disrupted, creating a large, chaotic wake that extends far behind the vehicle. This disruption is a constant drain on your engine’s power.

The most common mistake drivers make is leaving the roof box or even just the empty roof rack on the vehicle when not in use. The aerodynamic penalty is always present, regardless of whether the box is full or empty. This “empty box” mistake translates directly into wasted money. For a driver covering 15,000 miles annually, a 15% fuel penalty from an empty roof box can easily add up to $200-300 in unnecessary fuel costs per year at typical gas prices. Removing the box and racks when not needed is one of the single most effective actions you can take to restore your vehicle’s designed fuel efficiency.

When to Roll Up Windows and Use A/C to Reduce Drag?

The age-old debate of “windows down or A/C on” for better fuel economy has a definitive, physics-based answer. While it may feel more “natural” to cool off with an open window, at highway speeds, this choice imposes a significant aerodynamic penalty. Opening the windows creates a massive source of drag, as outside air rushes into the cabin, disrupting the smooth airflow along the vehicle’s sides and creating turbulence. This effect is akin to deploying a small parachute.

Conversely, the air conditioning (A/C) system puts a direct load on the engine, consuming power to run its compressor. The question, therefore, is which method consumes less energy at a given speed. Research by Oak Ridge National Laboratory for the U.S. government provides a clear crossover point: at speeds above 50 mph, using A/C is more fuel-efficient than driving with the windows open. The drag created by the open windows requires more energy to overcome than the energy needed to power the A/C compressor.

However, this is not a simple on/off rule. The optimal decision is dynamic and depends on your speed, vehicle type, and even the efficiency of your A/C system. A more nuanced framework can help you make the most efficient choice in any situation. A boxy vehicle, for example, already has high drag, so the additional drag from open windows is less impactful on a percentage basis compared to a very sleek, aerodynamic car.

- Under 35 mph: At low speeds, aerodynamic drag is minimal. The A/C compressor’s load is the dominant factor, so opening your windows is the more fuel-efficient choice for cooling.

- 35-50 mph: This is the transition zone. The most efficient choice depends on factors like outside temperature and your personal comfort. The penalty from either choice is relatively small.

- Above 50 mph: Aerodynamic drag is now a significant force. Close the windows and use the A/C. The energy saved by reducing drag outweighs the energy consumed by the A/C compressor.

- A/C System Efficiency: It’s also worth noting that modern A/C systems (post-2015) are significantly more efficient than older ones, making the argument for using A/C at high speeds even stronger.

How to Reduce Fuel Drag by 5% Using Shark Skin Textures?

Nature has often been the best aerodynamicist, and one of the most studied examples is the skin of a shark. Far from being smooth, it is covered in microscopic, tooth-like structures called dermal denticles or “riblets.” This unique texture manipulates the boundary layer of fluid flow, reducing turbulence and surface friction. This principle of biomimicry has been explored extensively in an attempt to reduce drag on everything from Olympic swimsuits to aircraft and, of course, automobiles.

The theory is sound: by creating a textured surface with precisely engineered grooves aligned with the direction of airflow, you can control the formation of small turbulent vortices near the skin. This keeps the overall airflow more attached and “laminar,” reducing what is known as skin friction drag. In laboratory settings, these riblet surfaces have shown the potential for impressive drag reductions, sometimes in the range of 3-8%.

However, translating this laboratory potential to the real world of automotive use has proven challenging. While companies like 3M have developed and tested drag-reduction films that mimic this shark-skin effect, the gains are more modest. Real-world applications of these films typically achieve a 1-3% improvement in fuel efficiency. The discrepancy arises from factors like the durability of the microscopic texture against road debris, dirt, and washing, as well as the difficulty of applying the film perfectly across a car’s complex curves. While a 5% reduction remains an ambitious target, the technology proves that even managing friction at the micro-level can have a measurable impact on the macro-level fuel bill.

Newtonian vs. Quantum Mechanics: Which Rules Apply to Nanotechnology?

A car moving through the air is a perfect illustration of classical, Newtonian physics. Forces like drag, mass, and acceleration are all governed by these predictable, large-scale rules. However, some of the most cutting-edge advancements in aerodynamics are now happening at a scale where the bizarre rules of quantum mechanics begin to play a role: the nanoscale. Nanotechnology allows engineers to manipulate materials at the molecular level to create surfaces with extraordinary properties.

While the car itself operates in the Newtonian world, its surface can be engineered with properties that are only possible due to quantum-scale phenomena. A prime example is the use of hydrophobic nano-coatings. These are ceramic or polymer coatings that, when applied to a car’s body and glass, create a surface that is extremely difficult for water to stick to. At the nano-level, the coating forms a structure of microscopic peaks and valleys.

This structure is so fine that water droplets cannot fully wet the surface; instead, they sit on the very tips of these peaks, held up by their own surface tension. This is a quantum-level effect dictating macro-level behavior. For aerodynamics, the benefit is most apparent in wet conditions. Instead of large water droplets or a sheet of water disrupting the smooth, laminar flow of air over the car, the hydrophobic surface forces water to bead up and roll off immediately. As modern Formula 1 teams have demonstrated, this allows the car to maintain a consistent and low-drag aerodynamic profile even in heavy rain, preserving performance and efficiency when it would otherwise be compromised.

Key Takeaways

- Aerodynamic drag increases with the square of velocity, making it the dominant factor in fuel consumption at highway speeds.

- A vehicle’s total drag is a product of both its shape (drag coefficient, Cd) and its size (frontal area, A); both must be considered.

- Simple actions, such as removing unused roof racks and adopting smoother driving habits, can yield fuel savings of 15-30%, far outweighing many expensive modifications.

How to Achieve 20% Fuel Savings Through Driving Habits Alone?

While vehicle design and modifications play a significant role, the single greatest influence on your car’s real-world fuel economy is the person behind the wheel. Your driving habits can either work with or against the principles of aerodynamics, and the difference can be staggering. EPA testing confirms that aggressive driving—characterized by rapid acceleration, hard braking, and high speeds—can lower gas mileage by 15-30% at highway speeds. This is because every time you accelerate hard, you are fighting a massive, non-linear increase in aerodynamic drag.

The key to “hypermiling,” or maximizing fuel efficiency through driving technique, is to treat momentum as a precious resource. The goal is to use the engine’s power to build momentum as efficiently as possible, and then preserve that momentum for as long as possible by minimizing the forces working against it—namely, braking and aerodynamic drag. This means looking far ahead, anticipating traffic flow to avoid unnecessary stops, and maintaining a smooth, steady pace.

An extreme (and dangerous) example of this principle is drafting, where driving closely behind a large truck can reduce aerodynamic drag by up to 90%. While this should never be attempted, it perfectly illustrates the power of managing airflow. A much safer and legal hypermiling technique is known as “Pulse and Glide.” This involves accelerating gently to a target speed (the “pulse”), then shifting to neutral and coasting with the engine off or at idle (the “glide”), letting momentum carry the vehicle. By repeatedly pulsing and gliding (e.g., between 55 and 65 mph), skilled drivers can achieve fuel savings of 20% or more. This technique essentially uses the engine in its most efficient range and then minimizes drag losses during the glide phase.

By applying these principles, you are no longer a passive consumer of fuel, but an active manager of your vehicle’s efficiency. Start today by observing how speed, acceleration, and your car’s profile interact on your daily commute to begin reducing the invisible aerodynamic tax on your wallet.