The difficulty of repairing modern cars isn’t just about added complexity; it’s the result of deliberate engineering that transforms vehicles into sealed, unserviceable ecosystems.

- Software locks and digital “tattletale” flags now prevent even basic component resets without dealership tools.

- Design choices that prioritize initial performance and fuel economy (like plastic parts and aerodynamics) directly compromise long-term durability and repair access.

- Key components like windshields and batteries are now integrated into the vehicle’s structure, making replacement a major, specialist-only operation.

Recommendation: Understanding this design philosophy is the first step for any DIY mechanic to know their true limits and fight for their right to repair.

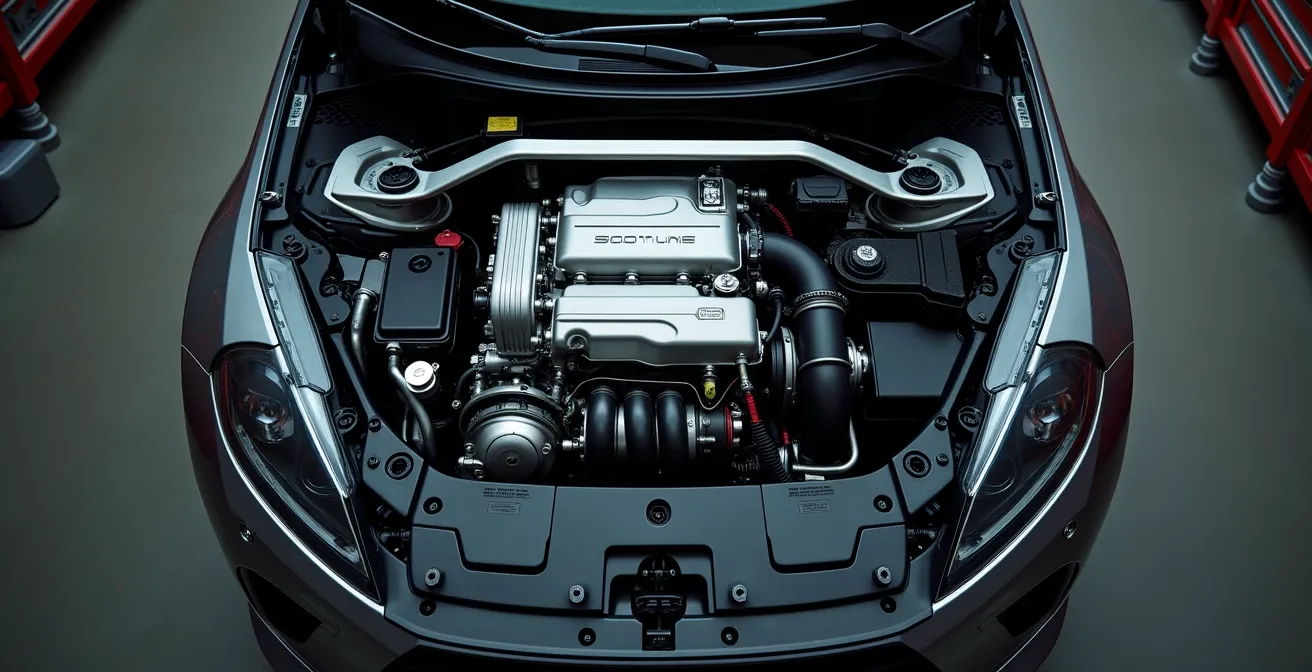

There’s a smell every shade-tree mechanic knows: a mix of old oil, hot metal, and the faint tang of gasoline. It’s the scent of a Saturday afternoon spent with a wrench in hand, knuckles bruised, learning the intimate language of an engine. You could once diagnose a problem by sound, fix it with a standard socket set, and drive away with the satisfaction of a job well done. Today, you pop the hood and are greeted by a monolithic sea of plastic. The engine is a fortress, and you don’t have the key.

The common complaints are well-known: “It’s all electronics,” or “They just want you to go to the dealership.” While true, these are just symptoms of a much deeper shift in automotive design. This isn’t a slow, accidental evolution toward complexity. It is a fundamental change in philosophy. Your car is no longer a collection of modular, replaceable parts; it has been engineered as a closed, integrated ecosystem.

But what if the true barrier isn’t just a new type of sensor or a proprietary bolt? What if the very materials, the structural assembly, and the invisible lines of code are all part of a deliberate strategy? This strategy prioritizes initial performance, fuel efficiency, and manufacturer control over the long-term serviceability that was once a cornerstone of car ownership. This isn’t just about making repairs harder; it’s a case of engineered unrepairability.

In this article, we’ll pull back those plastic covers and go beyond the surface-level frustrations. We will diagnose the eight key engineering decisions—from the plastic components that fail to the software that tethers your car to the dealer—that have systematically locked the home mechanic out of their own garage.

This guide breaks down the core technical and strategic shifts that define the modern, unrepairable vehicle. Follow along as we dissect each layer of this complex issue.

Summary: Why Are Modern Cars Becoming Impossible to Repair at Home?

- Why Plastic Engine Components Fail Faster Than Metal Ones?

- How to Use an OBD-II Scanner to Decode Modern Engine Errors?

- Turbocharged Efficiency or V6 Reliability: Which Lasts Longer?

- The Modification Mistake That Cancels Your Manufacturer Warranty

- When to Ignore the “Lifetime Fluid” Label and Change Your Oil?

- Chemical Glues or Gecko Adhesives: Which Is the Future of Assembly?

- How to Calculate the Center of Gravity for Asymmetrical Sculptures?

- How Does the Aerodynamic Profile of Your Car Impact Your Wallet?

Why Plastic Engine Components Fail Faster Than Metal Ones?

The first thing you notice under the hood of a modern car is the plastic. Intake manifolds, valve covers, oil filter housings—components that were once stout cast aluminum are now black polymer. The common wisdom is that this is simply to cut costs, but the reality is a classic engineering compromise: the performance-durability trade-off. These materials are chosen for their light weight, which contributes to better fuel economy and handling dynamics.

In fact, research from the Fraunhofer Institute demonstrates that plastic cylinder casings weigh up to 20% less than their aluminum counterparts, a significant saving. However, this benefit comes at a steep price. Unlike metal, which handles countless heat cycles with grace, plastic becomes brittle over time. Exposed to the intense temperature fluctuations of an engine bay, these parts warp, crack, and fail, leading to vacuum leaks, coolant loss, and other issues that were once rare.

This isn’t a new problem, but rather one that has evolved. As noted by a marketing leader in the industry, the initial foray into plastics had its issues. As Marianne Morgan of BASF Corp explains, “North American manufacturers had some failures with plastics back in the 1980s and 1990s, when their metal-based designs were not optimized for plastic material.” While designs have improved, the fundamental material limitation remains: plastic is simply not as resilient as metal in a high-heat, high-vibration environment, turning a long-term reliable component into a predictable failure point.

This shift from durable metal to lightweight plastic represents the first layer of engineered unrepairability, where long-term robustness is sacrificed for short-term performance metrics that look good on a spec sheet.

How to Use an OBD-II Scanner to Decode Modern Engine Errors?

For two decades, the On-Board Diagnostics (OBD-II) port was the DIY mechanic’s best friend. It was a universal key that unlocked the engine’s secrets, allowing anyone with a simple code reader to diagnose a check engine light. Today, that key no longer fits the lock. The port is still there, but a digital gatekeeper stands in the way, a core component of the car’s “digital tether” to the manufacturer.

The problem is so pervasive that research shows over 60% of independent repair facilities are now struggling to access the necessary data to service modern vehicles. They have the tools and the expertise, but they are being systematically locked out by automakers.

Case Study: The Security Gateway Module (SGW)

Automakers like Fiat Chrysler (FCA) and Mercedes-Benz have implemented a Security Gateway Module (SGW). This is a piece of hardware that acts as a firewall between the OBD-II port and the vehicle’s internal network (the CAN bus). While a generic scanner can still read basic fault codes, it is blocked from performing any active commands. Resetting an oil light, testing a sensor, or calibrating a new component is impossible without an authenticated, dealership-level tool. According to data from Autocare.org, this forces independent shops to turn away work, sending cars back to the dealer for tasks they are perfectly capable of performing.

This digital blockade turns your expensive diagnostic scanner into a read-only device. The frustration of having the right tool but being denied access is a reality for mechanics everywhere, transforming a simple reset into a costly trip to the dealership.

As the image illustrates, the physical connection is no longer the issue; the battle has moved to the software layer. This deliberate gatekeeping ensures that even if you can diagnose the problem, the power to authorize the solution remains exclusively in the hands of the manufacturer.

Turbocharged Efficiency or V6 Reliability: Which Lasts Longer?

The debate between a smaller, turbocharged engine and a larger, naturally aspirated one (like a V6) used to be a straightforward mechanical discussion. A turbo adds complexity, heat, and more moving parts, logically leading to a shorter lifespan. But in the modern automotive ecosystem, the answer is no longer found in the hardware alone. The true governor of a modern turbo engine’s life is its software.

A modern turbo engine’s lifespan is now intrinsically linked to its software for torque management, heat protection, and boost control. A simple software update can alter the physical stress on the engine.

– Drew Blankenship, Porsche Technician

This insight from a veteran technician is crucial. The Engine Control Unit (ECU) is no longer just a fuel-and-spark calculator; it’s an active system manager. It precisely controls boost pressure to prevent knocking, adjusts timing to manage heat, and limits torque in lower gears to protect the transmission. The engine’s physical durability is now entirely dependent on the integrity of this programming. An aggressive software tune from the aftermarket can push an engine beyond its designed thermal and mechanical limits, leading to premature failure.

Conversely, a manufacturer can issue an over-the-air update that de-tunes the engine to prevent a newly discovered weak point, changing the vehicle’s performance without the owner’s direct consent. This means the engine’s reliability is a moving target, defined not by the quality of its forged pistons, but by the lines of code that dictate its every move. The engine has become a hardware peripheral to the master computer, another tentacle of the integrated ecosystem.

The Modification Mistake That Cancels Your Manufacturer Warranty

For enthusiasts, modifying a car is a rite of passage. A new air intake, a cat-back exhaust, or a software tune were ways to personalize and enhance performance. Manufacturers have always had clauses to deny warranty claims if a modification caused a failure, but proving that link was often a gray area. That gray area has now vanished, replaced by a permanent, digital tattletale system.

The most notorious example of this is the “TD1” flag used by Volkswagen and Audi. This isn’t a simple error code; it’s a digital marker that is permanently burned into the ECU’s memory if it detects non-OEM software. Even if the car is flashed back to the stock program, the TD1 flag remains, visible to every dealer in the global network. It is an indelible scar that automatically voids any warranty claims on the powertrain.

Case Study: The Volkswagen/Audi TD1 Flag

As detailed by organizations like SEMA fighting for the right to modify vehicles, the TD1 system is the ultimate form of manufacturer control. The moment a technician plugs the car into the diagnostic system for any service, the network cross-references the ECU’s software signature. If the TD1 flag is present, warranty work on the engine or transmission can be immediately denied, no matter how unrelated the failure might be to the software modification. This digital marker effectively creates a permanent record of “unauthorized” activity, giving the manufacturer unilateral power to reject claims.

This surveillance isn’t limited to software. Modern cars are equipped with a suite of sensors that act like a black box, recording data that can be used to deny a warranty claim. The vehicle is actively logging evidence against its owner. These data points can include:

- G-force sensor data indicating aggressive driving or track use.

- Throttle position logs showing sustained periods of wide-open throttle.

- Peak RPM recordings that suggest racing or money shifting.

- Temperature data from engine and transmission sensors that could indicate overheating from abuse.

- Timestamps that correlate a failure event with a recent modification.

This level of monitoring turns the warranty into a conditional agreement where the driver must prove their innocence against a mountain of data, a far cry from the days when a warranty was a simple pact of trust.

When to Ignore the “Lifetime Fluid” Label and Change Your Oil?

One of the most misleading terms in modern automotive marketing is “lifetime fluid.” Found in sealed transmissions, transfer cases, and differentials, this label suggests the fluid inside is good for the entire life of the vehicle, requiring no service. This is a dangerous myth, built on a specific and self-serving definition of “lifetime.”

For a manufacturer, the “lifetime” of a vehicle isn’t how long you own it; it’s the designed service life, which is often the duration of the warranty period. As automotive experts point out, manufacturers typically define ‘lifetime’ as the designed service life of about 10 years or 150,000 miles. After that point, you are on your own. The fluid, which has been breaking down under heat and shearing forces for years, is now far past its effective-use window, and the component is on a fast track to failure.

To make matters worse, manufacturers enforce this planned obsolescence by making these components physically unserviceable. Transmissions are built without dipsticks or drain plugs, requiring special tools and procedures to check or change the fluid. It’s a deliberate act of engineered unrepairability.

The sealed unit shown above is a clear message: you are not welcome here. The business motive behind this is transparent. As automotive writer Bozi Tatarevic states, “Manufacturers are looking out for their franchised dealers and their ability to bring in customers for out-of-warranty repair work.” A transmission failure at 160,000 miles is a multi-thousand-dollar job that goes directly to the dealership, a failure that could have been prevented with a simple fluid change years earlier.

For any DIY mechanic, the rule is simple: there is no such thing as a lifetime fluid. If you plan to keep your vehicle beyond its warranty period, changing these fluids according to a severe-duty schedule (typically every 50,000-60,000 miles) is the single best investment you can make in its longevity.

Chemical Glues or Gecko Adhesives: Which Is the Future of Assembly?

The way cars are held together has fundamentally changed. The era of bolts, gaskets, and mechanical fasteners is giving way to the era of chemical bonding. High-strength structural adhesives are now used to assemble everything from body panels to chassis components. This shift, much like the move to plastics, prioritizes initial manufacturing efficiency and body rigidity over any consideration for future repair.

A prime example of this is the modern windshield. What was once a simple piece of glass held in by a replaceable rubber gasket is now a structural component of the vehicle’s unibody. It contributes significantly to chassis stiffness and is critical for proper airbag deployment. This is achieved by bonding it directly to the frame with powerful urethane adhesives. A simple parking lot fender-bender that slightly tweaks the frame can now lead to catastrophic repair bills, as a minor parking lot bump now results in an average cost of $2,500 to fix on an adhesive-intensive vehicle.

Case Study: The Evolution of Windshield Installation

The journey of the windshield from a simple, mechanically-fitted part to a complex, integrated system module is a perfect microcosm of engineered unrepairability. Early cars used gaskets that a home mechanic could replace in an afternoon. Today, replacing a windshield is a specialist job. The urethane bond must be precisely cut, and the new glass installed in a climate-controlled environment. Furthermore, with the integration of ADAS (Advanced Driver-Assistance Systems) cameras, a replacement now requires an expensive recalibration at a dealership to ensure features like lane-keep assist and emergency braking function correctly. A simple glass replacement has become a complex electronic and structural procedure.

This move towards chemical assembly means that disassembly is often destructive. Panels cannot be unbolted; they must be cut apart. This not only makes repairs exponentially more expensive and time-consuming but also pushes many collision repairs beyond the threshold of being economically viable, leading to more vehicles being written off for otherwise repairable damage.

How to Calculate the Center of Gravity for Asymmetrical Sculptures?

While the title seems abstract, the principle of managing a vehicle’s center of gravity (CoG) is a primary driver behind component placement—and a major source of frustration for mechanics. To achieve optimal handling and stability, automotive engineers strive to place the heaviest components as low and as close to the center of the vehicle as possible. This is a sound engineering principle with a terrible side effect for serviceability.

Placing heavy components like the battery, ECU, or ABS module as low and centrally as possible for handling performance results in these components being buried under floors, behind dashboards, or deep in the engine bay.

– Engineering Analysis, Automotive Design Principles Study

This is why a simple battery change can now require removing a wheel and fender liner, or why accessing the ABS module might involve dismantling the entire dashboard. The components aren’t placed for ease of access; they are placed to serve the physics of performance. The mechanic’s convenience is not a variable in the design equation. This philosophy reaches its ultimate conclusion in the design of modern electric vehicles.

Case Study: The EV Skateboard Chassis

Electric vehicle “skateboard” platforms are a masterclass in CoG optimization. A massive, heavy battery pack forms the floor of the car, creating an incredibly low and stable center of gravity. This design provides exceptional handling and safety. However, it also creates the ultimate unrepairable-at-home component. The battery is not just a power source; it is a stressed, structural member of the chassis. A failure of a single cell group or module often means the entire thousand-pound, high-voltage pack must be dropped and replaced—a job that is impossible without a vehicle lift and specialized equipment. It perfectly solves the CoG problem while creating an absolute barrier to DIY repair.

The relentless pursuit of a lower center of gravity has led directly to components being buried in the most inaccessible locations imaginable. It is a clear case where performance design has completely overridden any thought for the person who will one day have to service the vehicle.

Key Takeaways

- Modern cars are not modular machines but integrated ecosystems where hardware, software, and structure are interdependent.

- The “digital tether”—through software locks and data logging—gives manufacturers unprecedented control over diagnostics and repairs, effectively disabling aftermarket tools.

- Many design choices that improve initial performance or meet regulatory targets (lightweight plastics, aerodynamics, low CoG) inherently reduce long-term durability and service access.

How Does the Aerodynamic Profile of Your Car Impact Your Wallet?

In the quest for every last fraction of a mile per gallon, aerodynamics has become a dominant force in car design. Smooth, uninterrupted surfaces, active grille shutters, and extensive underbody paneling all help a car slice through the air more efficiently. While this benefits your fuel budget, it delivers a direct hit to your wallet when it comes to maintenance and repair. Every one of these aero features adds a layer of complexity and cost.

What appears to be a simple, sleek design is, in reality, a fragile and expensive puzzle. Accessing even basic service items now requires the painstaking removal of large plastic panels held on by dozens of single-use clips that are designed to break upon removal. A simple oil change or belt inspection can be preceded by an hour of labor just to get the car “undressed.”

These aerodynamic components are not just passive panels; they are often active systems that introduce new and costly failure points. An active grille shutter that gets stuck can cause engine overheating, and replacing the motor and assembly can cost hundreds of dollars. The smooth, integrated bumpers that look so clean are now packed with sensors for parking assist and collision avoidance. A minor parking lot nudge that once required a simple bumper respray now mandates a full bumper replacement plus a costly ADAS recalibration to ensure the safety systems work correctly.

Your Aerodynamic Cost Audit Checklist: Points to Check

- Underbody Panels: Inspect for the number of plastic panels that must be removed for basic services like oil changes or transmission access. Note the labor time this adds.

- Fasteners: Count the number of single-use clips and fasteners holding these panels. Inventory how many break during a typical service and must be replaced.

- Active Aero Components: Identify active grille shutters or spoilers. Research their replacement cost and common failure modes for your specific model.

- Integrated Bumpers & Sensors: Check if bumpers contain embedded sensors (parking, blind spot). Confirm if replacement requires a mandatory, dealership-only ADAS recalibration.

- Aero Wheel Covers: Determine if decorative or aerodynamic wheel covers block access to lug nuts or brake components, complicating routine tire and brake work.

The sleek, efficient profile of a modern car is a carefully constructed illusion. Underneath lies a network of fragile, expensive, and access-blocking components that have turned routine maintenance into a costly and frustrating ordeal. It is the final layer of the integrated ecosystem, where even the pursuit of efficiency is engineered to drive you out of your garage and into the dealership’s service bay.

The days of the Saturday afternoon tune-up may be gone, but understanding the forces at play is the first step toward reclaiming your rights as a vehicle owner. By being aware of these systemic barriers, you can make more informed purchasing decisions and lend your voice to the growing “Right to Repair” movement, which seeks to restore balance and put the tools back in the hands of the people.